It is home of the Texas famous Blue Bell Ice Cream and Blinn Junior College. My ticket to study engineering in America was based on a music scholarship, but that’s another subject.

I was a wet behind-the-ears black kid that spoke with an accent in a country town. The black American kids were suspicious of me, the white American kids were curious, and the Hispanic American kids giggled when I spoke to them in Spanish. I hung out with Peruvian, Argentinian, Guatemalan, and Venezuelan friends most of that year. We were all strangers in a new land away from our parents for the first time who shared one thing in common — we could all communicate in Spanish and when strange things happened we could enter our cocoon. It is amazing how quickly and quietly human beings adapt.

We were walking down one of the few commercial streets in Brenham when some guys in a pickup truck just started shouting nigger and, if I remember correctly, something about being in the wrong part of town. It was directed solely at me because, while we were all Latinos walking down that street, I was the only black one.

I remember going to Padre Island for spring break, six of us packed like sardines in my car. I remember getting to the beach house and the coldness with which I was treated on the island, compared to my geographic brothers and sisters from South and Central America. Funny thing is they never had a clue.

I always knew Blinn was a stepping stone to move up, and I moved up to The University of Texas at Austin (UT) after a year at Blinn. I had no problem getting in on my own merit, but most of my friends assumed I got in thanks to some quota (they did not realize as a foreigner I did not qualify). Both students and professors in many instances went out of their way to remind me that I was an “other.” I rallied the campus for UT’s divestiture from South Africa given their overtly brutal apartheid system. I understood that fighting injustices somewhere else helped to hold up a mirror to the injustices we faced locally.

I remember being stopped many times by the police. It’s not that I was a bad driver. Most of the stops seemed to have only to do with a desire to question me. It was never confrontational. I did as I was told. You see, where I am from, Panama, a dispute with an officer guarantees a cracked skull with no legal recourse, so the cops in Austin likely thought I was a model citizen. From a young age, I always knew when and where to engage. I adapted.

When I graduated from UT and went to work, I encountered the same preconceived notions. But work isn’t the cops. I was vocal and never took any crap. Suffice it to say I had 5 jobs in 5 years and finally formed my own company. When my company became fairly successful I moved to Kingwood, a nice suburb with a lot of trees and a very good school system for my daughter.

My first memorable experience in Kingwood was walking in the trails and passing a white woman who immediately held her purse tightly and looked at me with horror. I looked at her and simply shook my head, seething. Another time I went cycling with one of my new friends and stopped into a convenience store. When we left the store my friend simply said, “I get it now.” I guess I was his first black friend. Inside that store, he saw how differently a person with my skin color is treated.

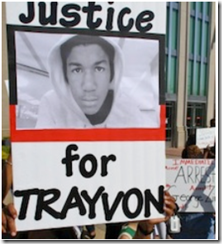

It is 2013. I’ve been living in the US for 34 years. The fact that we still mourn our Trayvon Martins means there is a lot more work for us to do. Preconceived notions and irrational hatred still pollute human interactions. Sometimes, these weaknesses are codified into law. Black boys and men are stereotyped. Incarceration rates and crime rates are pointed to as justification for unequal treatment, and fodder for false narratives. These numbers do not take into account the fact that young men in my neighborhood, a predominantly white neighborhood, do not go to jail for infractions they confess to, while young men in other neighborhoods are arrested indiscriminately. It does not reflect that sentences on minorities are harsher and as such their chances of being granted parole and rehabilitation are smaller.

There are many Trayvon Martins out there. Many. It is sad that we have lost this beautiful young man. It is sad, also, that similar incidents occur frequently with very little news coverage. Trayvon’s case seems to resonate, perhaps because he was 17, good looking, and did not have a record. Every mother irrespective of color could envision him as their son. Every father as well. And that touches our hearts. We sense the pain that Trayvon’s real parents must feel. In the America we envision — an America where there is no “other” — such compassion for our fellow human beings is commonplace, and no one’s son deserves to die this way.

Many are emphasizing the fact that Mr. Zimmerman looks Hispanic. I’m not sure why. Does this irrelevant detail somehow exonerate him from suspicion of a hate crime? Do they think that by presenting a narrative of “minority-on-minority crime,” they can diminish the meaning of this event? Do they hope that the news networks will lose interest if they are reminded that typically they have ignored minority-on-minority crime? What is important to note is that within the Hispanic community there are many races. The racism we know in this country is found in every country in Latin America. Many of my South and Central American friends could pass for white just as Mr. Zimmerman can. They still struggled to assimilate. Ultimately they did.

Many Americans want to see the Trayvon Martin case as a potential learning experience. I do not think this is likely because we are so resistant to the only real solution, which involves everyone getting out of our comfort zones. The trial is probative. The attempt to make dead Trayvon Martin a stereotypical dangerous violent black thug is in full vogue. Some attempt to assume the only reason Trayvon would have been shot is that ‘he’ caused Zimmerman to do it. Many willfully attempt to make this plausible even though Zimmerman followed Trayvon as if he was a criminal or a prey.

Citizens must speak up against the “no-gun-control-bullies” that use intimidation tactics and loads of money to insist upon lawlessness when it comes to deadly weapons. If we are to resolve real racial problems we each must take it upon ourselves to lead by example — speak with honesty, and allow others to feel free to speak with honestly about what is in their hearts and minds without holding it against them. Only when our feelings about one another are revealed can we address, adjust, correct, or corroborate them. Only when we’ve begun and maintained an open conversation about race and racism can we see past our preconceived notions and truly hear and see one another.

Racism is not a problem with preassigned blame. Racism is simply a problem, and it belongs to all of us.

Minorities do not have a monopoly on victimhood. The white majority does not have a monopoly on responsibility, or guilt, or anger toward those who would have them feel guilty. The slate must be wiped clean. We must carry no grudges, and begin by asking ourselves and one another, “Is this the way we want to go on living? Divided? Lacking trust? Lacking civility? Lacking patriotism (not only love of America, but also love of Americans)? Some of us resist asking such questions with openness because we fear we might end up losing something we think we now possess. But whatever it is we have now with the status quo, is it so wonderful that we wouldn’t risk it for a higher level of understanding, and, a more fair, inclusive, and united country?