by Michael Hanchard

Michael Hanchard, a Professor in Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, is the author of The Spectre of Race: How Discrimination Haunts Western Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2018).

Forms of exclusion have helped democracies distinguish between citizens and non-citizens since the founding of democracy itself, all the way back to classical Athens.

Not too long ago, a certain politician made the following statement from the floor of the U.S Congress: “I believe that possibly statistics would show that the Western European races have made the best citizens in America.” They are, he continued, “more easily made into Americans.” Idaho Rep. Dr. John Travers Wood, speaking in 1952, hoped to amend American immigration policy and lower quotas for non-white migrants coming into the United States.*

Although Wood’s proposed amendment to the McCarran-Walter Act was rejected by a vote of 70–25, his logic for that amendment rings familiar to most anyone paying attention to immigration policy in the Trump Era. The Trump Administration’s ban on “all Muslims” coming from select countries, its separation of families along the U.S./Mexico border, or the president’s reference to black immigrants coming from their “shithole counties” have all served as touchstones of today’s, especially intolerant U.S. immigration regime.

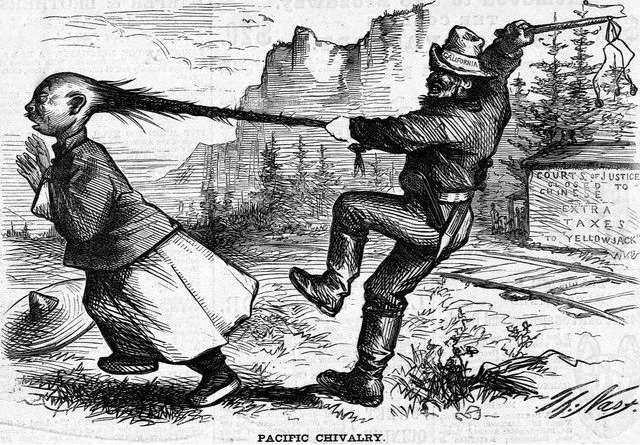

Wood’s remarks, made more than three generations ago, remind us that the current administration is by no means the first in the U.S. to adopt exclusionary ideologies and policies regarding non-white immigrants. Nor is it a novel thing to use, as Trump staffers often do, so-called scientific proof, in this case, statistics, to argue that Western European races can more easily transform into Americans and by extension, citizens.

Exclusionary barriers to citizenship have been a part of the U.S. republic from its inception. Moreover, many democratic polities, not just the United States, have created and administered barriers to political membership based on nationality, religion, ethnicity and what is often referred to as race. Though not always known as “race,” forms of exclusion have helped democracies distinguish between citizens and non-citizens since the founding of democracy itself, all the way back to classical Athens.

Moments of geopolitical crisis, such as that experienced by the Greeks during the Greco-Persian Wars or the United States during World War II, generate anxieties about national security and increase the tendency among certain citizens, particularly those of a dominant ethnonational or so-called racial group, to associate the citizenry with particular types of people, and not the actual exercise of citizenship through the assumption of rights, duties, and responsibilities.

Foreigners, women, the laboring classes, and, in many cases, slaves have all, by turns, served as democracies’ necessary outliers. The menace to democracy in this and earlier moments in U.S. and global history has often been based upon perceived origin. Japanese internment is one example, but a particularly poignant one. Differences in origin, even though the Nisei (First generation Japanese Americans) were actually born in the United States, provided enough grounds to delimit their citizenship.

In other words, democracies throughout history have institutionalized exclusionary, anti-democratic practices. They have maintained a sharp distinction between members of their societies (the people who simply live there) and members of their polities (the people who actually influence the political process). As democratic institutions maintain barriers to civic membership, they must always justify that exclusion.

But what is the endgame or ultimate objective of these highly selective, discretionary and racialized citizenship regimes in which migrants coming from Central America are now met with virtual imprisonment and separation of children from their parents and loved ones, while immigrants – particularly white immigrants – crossing the northern border into the United States are met with no such barriers to entry? Whether in the United States, Germany, Italy, France or Britain, advocates for selective, ethnos-based immigration restrictions share an understanding of their national histories that are deeply flawed; somewhere in the not-too-distant past and indeed, since time immemorial, their country was crowded with people who were, almost exclusively, just like them. Consequently, they pursue a quest for homogeneity, linking immigration, citizenship and racial regimes within a more comprehensive vision of a political community. In this nostalgic yet false vision, civic, even societal membership remains based upon some group born of the same soil or “homeland.”

This idea too, has its origins in the past, though not a past most people would associate with the practice of democracy. The modern nation-state, especially its democratic, republican iterations, was made in the image of classical Athens. The nation-state conjoins a loyal, national population residing in a territory to a unitary state that presides over both territory and population. Unlike earlier moments in human history, where towns, villages, kinship, empires, principalities, and nomads were far more recognizable modes of human community than nation-states, nation-states provide containers to situate governments and populations within the same territorial unit.

Witness the range of societies, some democratic, some not, where an agitated quest for population homogeneity has led to social policy and law that further discriminate and marginalize minority populations. Not just the United States, but Italy, France, Germany, as well as countries like Afghanistan and Syria, currently have political forces which thrive on this long cherished but patently false belief that their societies and political communities were, once upon a time, religiously, ethnonationally or culturally homogeneous. Nazi Germany’s genocidal treatment of non-Aryans is perhaps the most readily identifiable example, to which we can add Hitler’s attempts to redesign the former Soviet Union and much of Eastern Europe by population transfer, prompted by their version of racial hierarchy.

In the contemporary moment, the overwhelming majority of cases where immigration is viewed as a problem are not problems of immigration. Instead, they are problems of perception and ultimately, a nation-states’ ethnonational and racialized history. The fears and anxieties often reveal long-standing ethnonational, religious and racist biases, which in turn become embedded into governmental policy and public debate.

The lesson I would like to emphasize here for our contemporary moment is that population homogeneity, like the category of the foreigner and citizen, is a political artifact, not something we find ready-made in the world, not something that ever existed. So much of the origin tales told by various ultra-nationalist and xenophobic movements in nation-states rely on stories and genealogies that are themselves mythical.

Disagreements within Europe and the United States regarding who is, and who can be, a European or a citizen of the United States, can be boiled down to the following questions: Shall we let any of these outsiders in, and if so, which ones? By what criteria shall we include some people and exclude others? Once allowed in, who should be encouraged to leave, and who should be encouraged to stay? In answering these questions, policymakers and the average citizen may do well to consider the possibility that democracy itself as historically and politically practiced (not its idealized forms) may be part of the problem and not necessarily the solution to intolerance and inequality in the contemporary world.

Democracy is in need of significant repair. Those statistics that Rep. Wood, Donald Trump, and so many others have summoned as proof, yet again, of white immigrant supremacy, remain elusive, in part because the “proof” they are supposed to provide don’t hold up to historical scrutiny, nor to the desire of many citizens and non-citizens of the world to live in democratic polities but without the exclusions of their Athenian, European, and U.S. predecessors.

- “Revision of Laws Relating to Immigration, Naturalization, and Nationality,” Congressional Record (82nd Congress. Vol. 98, April 23, 1952), pp. 4314–16.