Mary Jo McConahay is the author of “The Tango War, the Struggle for the Hearts, Minds and Riches of Latin America in World War II” (St. Martin’s Press)

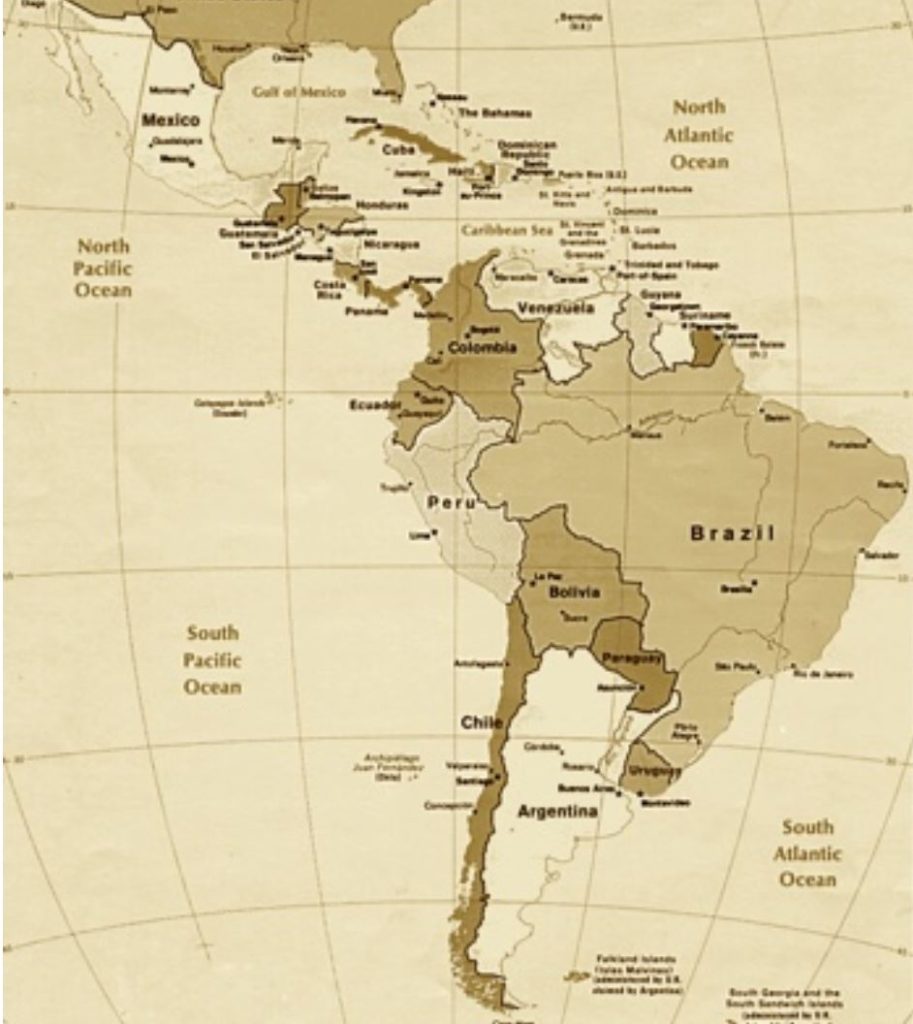

In the run-up to World War II, Latin America was up for grabs and countries that would become the Axis held the upper hand. Latin skies were ruled by airlines owned by German immigrants, some still loyal to the fatherland. Or by Italians, who flew a route that transported spies back and forth and delivered contraband vital to the war effort, like industrial diamonds and platinum, to the heart of the Reich. Mexico sent oil to Hitler and Mussolini, Germany and Japan bought up Brazilian rubber.

Today the United States is dismissing Latin America as our backyard in a way it has not done since those dangerous pre-war years, allowing other countries, especially China, to wield new influence. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, most Latin nations eventually declared for the Allies. But not before a delay that favored the enemy, jeopardizing U.S. security. It is worth remembering that volatile period of the late 1930s and early 1940s now when hemispheric solidarity is on the rocks.

President Trump’s vow to build an impenetrable wall on the southern border of the United States is a campaign promise run amok but also a signal to Latin countries that they will be kept at a distance. Earlier this year the president failed to attend the eighth Summit of the Americas, held in Lima, Peru, the single gathering where regional heads of state can talk face to face. Held every three years since 1994, the summits are a venue where Washington can push its policy objectives in a collegial way – this would have been a good year to shape a regional response to Venezuela; Trump was the first U.S. president to absent himself. Meanwhile, Washington is unraveling the Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Mexico, and after more than two years of insulting our closest southern neighbor, slapped crippling tariffs on metals from friendly countries including Mexico. Peru, Chile and Mexico are members of the twelve-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership; Trump pulled the United States out of the TPP on his third day in office.

As Washington cedes political leadership worldwide, Asia – especially China — has stepped into the vacuum in Latin America with loans, infrastructure projects, a charm offensive. China is importing record amounts of iron ore from Brazil, while Chile and Peru now supply half of its copper imports. China has replaced the United States as the major trading partner of Brazil, South America’s largest economy, and of Chile and Peru. As the administration unsettles NAFTA, Mexico too is likely to turn more to China.

Beyond diplomacy and balance sheets, alienation from the United States grows again in the Latin American street. The aftermath of Barack Obama’s election in 2008 was the first time in more than thirty years as a journalist in Latin America that I saw American flags in the windows of ordinary houses, a sign of friendship. Rapprochement with Cuba (later reversed by Trump) was enormously popular. A Rio lunch spot offered an “Obama Special” on its sidewalk sandwich board. When Trump was elected his image appeared in local markets in the shape of piñatas, those papier-mâché figures that party-goers like to hang on a string and strike with a stick until they tear apart.

In May, the administration announced it would end protected status (TPS) for 450,000 persons from El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras and Haiti who fled natural disasters – some have lived in this country for more than twenty years. Their deportations will break up families here but also wreak unbearable pressure on the largely poor Latin countries to which they return. The way we treat immigrants resonates quickly throughout the continent on television and social media, like the photo of a mass trial of immigrants wearing orange prison jumpsuits in a Pecos, Texas, courtroom, uncomfortably recalling the mass trials of dictatorships. Or like stories of the dark practice of separating children from their undocumented parents to deter immigration.

And what could resound more hideously than the spread of dehumanizing language, coming from the top, about some Latin immigrants? Mexico sent “rapists” to the United States, Trump said, on the day he announced his presidential campaign. In a Nashville rally he “worked his audience…into a frenzy” by evoking the term he has used for certain undocumented immigrants including members of criminal gangs, the New York Times reported.

“What was the name?” Trump baited.

“ ‘Animals!’ his cheering supporters screamed back.”

Eighty years ago, in July 1938, President Roosevelt called for an international conference to address the resettlement of hundreds of thousands of Jews being forced out of the Reich. The Evian Conference, held at a splendid hotel on sparkling Lake Geneva, failed miserably; except for the Dominican Republic, no country, including the United States, agreed to take refugees. “NOBODY WANTS THEM” gloated a headline in the German newspaper Volkischer Beobachter. Scholars have called Evian “Hitler’s green light for genocide.”

Migrants forced to return to Latin America do not face death camps. But they face death threats. The civil wars that took hundreds of thousands of lives three decades ago continue to percolate with political and random violence. Yet the atmosphere that prevailed at Evian seems to be repeating itself, at least in the United States. In April and May, a Pew Research Center Poll determined that 43 percent of Americans (68 percent of Republicans) said the country had “no responsibility” to admit refugees, for instance. Washington accepted more than 15,000 refugees fleeing Syria in 2015, eleven in 2018. Migrants and refugees have become the undesirables of our day.

The Washington trend toward nativism and withdrawal from the world stage mirrors pre-war U.S. conditions that complicated relations with Latin America, a necessary — natural— ally then and now. “From this day forward, it’s going to be only America First,” Trump said on inauguration day, echoing the name of the isolationist mass movement that threatened FDR’s presidency and, had it succeeded, would have kept the United States out of World War II.

“The vast resources and wealth of this American Hemisphere constitute the most tempting loot in all the round world,” Roosevelt told a national radio audience in his Arsenal of Democracy speech on December 29, 1940, addressing those who assumed the United States and Latin America would be left in peace if we kept to ourselves. His words set off a debate about America’s role in the world that begs to take place again.