Robert Brent Toplin is Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington and previously was a professor of history at Denison University. He has published several books about history, politics and film. Toplinrb@uncw.edu

Donald Trump has been president for only two of the ten years of America’s economic expansion since the Great Recession, yet he eagerly takes full credit for the nation’s advancement. It has been easy for him to boast because he had the good fortunate to occupy the White House during a mature stage of the recovery. The president’s fans attribute booming markets and low unemployment to his leadership even though Trump’s words and actions at the White House have often broken the economy’s momentum. In recent months, especially, Trump’s interference in business affairs has put U.S. and global progress at risk.

An article that appeared in the New York Times in May 2019 may offer some clues for understanding why the American president has been less than skillful in managing the country’s financial affairs. Tax records revealed by the Times show that from 1985 to 1994 Donald Trump lost more than a billion dollars on failed business deals. In some of those years Trump sustained the biggest losses of any American businessman. The Times could not judge Trump’s gains and losses for later years because Trump, unlike all U.S. presidents in recent decades, refuses to release his tax information. Nevertheless, details provided by the Times are relevant to a promise Trump made during in 2016. Candidate Trump advertised himself as an extraordinarily successful developer and investor who would do for the country what he had done for himself. Evidence provided by the Times suggests that promise does not inspire confidence.

Trump’s intrusions in economic affairs turned aggressive and clumsy in late 2018. An early sign of the shift came when he demanded $5.7 billion from Congress for construction of a border wall. House Democrats, fresh off impressive election gains, stated clearly that they would not fund the wall. The president reacted angrily, closing sections of the federal government. Approximately 800,000 employees took furloughs or worked without pay. Millions of Americans were not able to use important government services. When the lengthy shutdown surpassed all previous records, Trump capitulated. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that Trump’s counterproductive intervention cost the U.S. economy $11 billion.

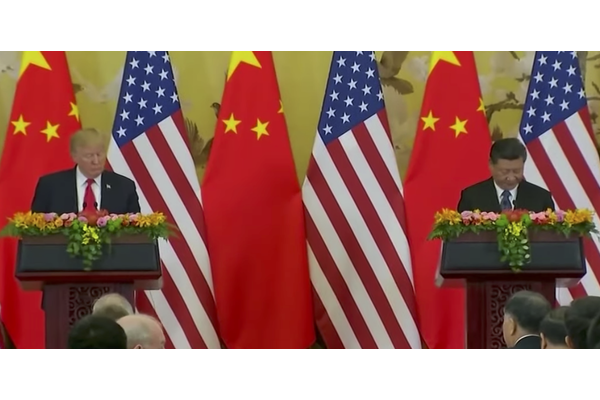

President Trump’s efforts to engage the United States in trade wars produced more costly problems. Trump referred to himself as “Tariff Man,” threatening big levies on Chinese imports. Talk of a trade war spooked the stock markets late in 2018. Investors worried that China would retaliate, inflating consumer prices and risking a global slowdown. Then Trump appeared to back away from confrontations. The president aided a market recovery by tweeting, “Deal is moving along very well . . . Big progress being made!”

Donald Trump claimed trade wars are “easy to win,” but the market chaos of recent months suggested they are not. When trade talks deteriorated into threats and counter-threats, counter-punching intensified. In May 2019, China pulled away from negotiations, accusing the Americans of demanding unacceptable changes. Trump responded with demands for new tariffs on Chinese goods. President Trump also threatened to raise tariffs against the Europeans, Canadians, Japanese, Mexicans, and others. U.S. and global markets lost four trillion dollars during the battles over trade in May 2019. Wall Street’s decline wiped out the value of all gains American businesses and citizens realized from the huge tax cut of December 2017.

President Trump’s confident language about the effectiveness of tariffs conceals their cost. Tariffs create a tax that U.S. businesses and the American people need to pay in one form or another. Tariffs raise the cost of consumer goods. They hurt American farmers and manufacturers through lost sales abroad. They harm the economies of China and other nations, too (giving the U.S. negotiators leverage when demanding fairer trade practices), but the financial hits created by trade wars produce far greater monetary losses than the value of trade concessions that can realistically be achieved currently.

Agreements between trading partners are best secured through carefully studied and well-informed negotiations that consider both the short and long-term costs of conflict. The present “war” is creating turmoil in global markets. It is breaking up manufacturing chains, in which parts that go into automobiles and other products are fabricated in diverse countries. Many economists warn that the move toward protectionism, championed especially by President Trump, can precipitate a global recession.

Trump’s approach to trade had unfortunate effects early in the Great Depression. In 1930 the U.S. Congress passed the protectionist Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act that placed tariffs on 20,000 imported goods. America’s trading partners responded with their own levies. Retaliatory actions in the early 1930s put a damper on world trade and intensified the Depression. After World War II, U.S. leaders acted on lessons learned. They promoted tariff reduction and “free trade.” Their strategy proved enormously successful. Integrated trade gave nations a stake in each other’s economic development. The new order fostered seventy years of global peace and prosperity. Now, thanks to a president who acts like he is unaware of this history, the United States is promoting failed policies of the past.

It is not clear how the current mess will be cleaned up. Perhaps the Chinese will bend under pressure. Maybe President Trump will agree to some face-saving measures, accepting cosmetic adjustments in trade policy and then declaring a victory. Perhaps Trump will remain inflexible in his demands and drag global markets down to a more dangerous level. Markets may recover, as they did after previous disruptions provoked by the president’s tweets and speeches. Stock markets gained recently when leaders at the Federal Reserve hinted of future rate cuts. It is clear, nevertheless, that battles over tariffs have already created substantial damage.

Pundits have been too generous in their commentaries on the president’s trade wars. Even journalists who question Trump’s actions frequently soften their critiques by saying the president’s tactics may be justified. American corporations find it difficult to do business in China, they note, and the Chinese often steal intellectual property from U.S. corporations. Pundits also speculate that short-term pain from tariff battles might be acceptable if China and nations accept more equitable trade terms. Some journalists are reluctant to deliver sharp public criticism of Trump’s policy. They do not want to undermine U.S. negotiators while trade talks are underway.

American businesses need assistance in trade negotiations, but it is useful to recall that the expansion of global trade fostered an enormous business boom in the United States. For seven decades following World War II many economists and political leaders believed that tariff wars represented bad policy. Rejecting old-fashioned economic nationalism, they promoted freer trade. Their wisdom, drawn from a century of experience with wars, peace and prosperity, did not suddenly become irrelevant after Donald Trump’s inauguration. Unfortunately, when President Trump championed trade wars, many Americans, including most leaders in the Republican Party, stood silent or attempted to justify the radical policy shifts.

Since the time Donald Trump was a young real estate developer, he has demonstrated little interest in adjusting beliefs in the light of new evidence. Back in the 1980s, when Japan looked like America’s Number One economic competitor, Donald Trump called for economic nationalism, much like he does today. “America is being ripped off” by unfair Japanese trade practices,” Trump protested in the Eighties. He recommended strong tariffs on Japanese imports. If U.S. leaders had followed Donald Trump’s advice in the Eighties, they would have limited decades of fruitful trade relations between the two countries.

America’s and the world’s current difficulties with trade policy are related, above all, to a single individual’s fundamental misunderstanding of how tariff’s work. Anita Kumar, Politico’s White House Correspondent and Associate Editor identified Trump’s mistaken impressions in an article published May 31, 2019. She wrote, “Trump has said that he thinks tariffs are paid by the U.S.’s trading partners but economists say that Americans are actually paying for them.” Kumar is correct: Americans are, indeed, paying for that tax on imports. This observation about Trump’s misunderstanding is not just the judgment of one journalist. Many commentators have remarked about the president’s confusion regarding who pays for tariffs and how various trading partners suffer from them.

The United States’ economy proved dynamic in the decade since the Great Recession thanks in large part to the dedication and hard work of enterprising Americans. But in recent months the American people’s impressive achievements have been undermined by the president’s clumsy interventions. It is high time that leaders in Washington acknowledge the risks associated with the president’s trade wars and demand a more effective policy course.

It’s the economy, economy, economy, economy, economy, economy.