Scientists (and economists and business people) love to create models to help predict future outcomes as a way to direct planning and preparedness efforts. Climatologists specifically love to create models of how the planet and its various natural systems and cycles will react with the input of way too many greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere. Climate science has come a long way since its early days a few decades back, but most of what we think will happen regarding global warming comes from global climate models—that is, predictions based on lots of empirical data about how much global average temperature is expected to rise and by when.

“Global climate models (GCMs) simulate the interactions between the atmosphere, ocean and land to project future climate, based on assumptions about future emissions of greenhouse gases,” reports the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington (UW).

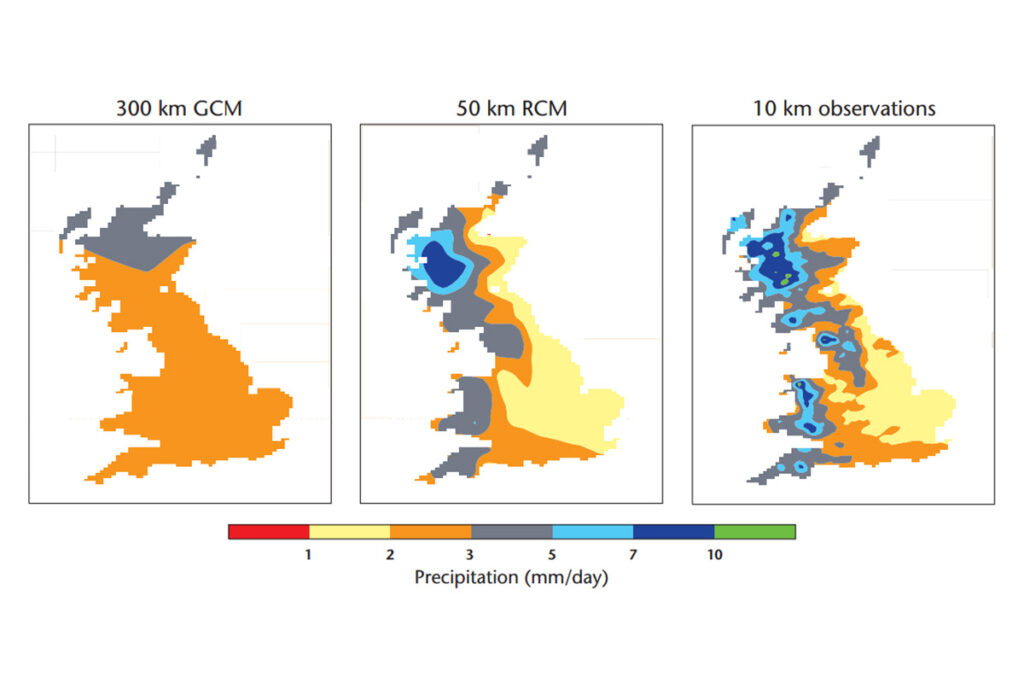

According to ClimatePrediction.net, a volunteer computing and climate modeling project out of the UK’s University of Oxford, global climate models (GCMs) are designed to calculate what the climate is doing (in terms of wind, temperature, humidity, etc.) at a number of discrete points on the Earth’s surface as well as in the atmosphere and out at sea. The points are then laid out in a grid covering the planet’s surface. The more points at play, the finer the resolution (and accuracy) of the model.

Nowadays climate researchers are applying what they have learned thus far to look in more detail on a regional basis, especially given that climate change has not only large-scale but also local consequences. These so-called regional climate models (RCMs) work by magnifying the resolution of GCMs in a small, limited area of interest, typically within a 3,000 square mile radius. Only by creating and analyzing RCMs can we assess the influence of myriad fixed geographic conditions and other local factors such as land height, land use, lakes, sea breeze, mountain ranges and localized weather patterns on climate impacts for a particular metropolitan area, state or country.

“For the practical planning of local issues such as water resources or flood defenses, countries require information on a much more local scale than GCMs are able to provide,” adds ClimatePrediction.net. “Regional models provide one solution to this problem.”

UW’s Climate Impacts Group has been able to leverage its expertise in global and now regional climate modeling to do groundbreaking research into the likelihood of things like floods in the Pacific Northwest, expected moisture flux convergence and ensuing drought in the Southwest, and, even further afield, projected climate change and impacts in Southeast Asia. The analytical techniques being pioneered at UW are being shared with researchers around the world with the hope that more and more scientists will start to run RCMs in their own regions to help planners plan and improve people’s lives despite the warming climate.

GCMs and RCMs are both important tools in figuring out how to cope with the effects of climate change, whether a worst case scenario is borne out or something not quite so cataclysmic.

CONTACTS: ClimatePrediction.net, ClimatePrediction.net; UW Climate Impacts Group, cig.uw.edu.

EarthTalk® is produced by Roddy Scheer & Doug Moss for the 501(c)3 nonprofit EarthTalk. See more at https://emagazine.com. To donate, visit https://earthtalk.org. Send questions to: question@earthtalk.org.