How do we defeat coronavirus?

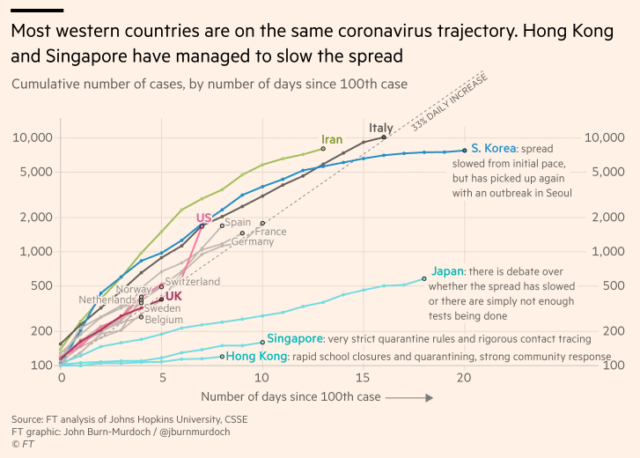

Every news outlet ought to have a chart like this one, from the Financial Times, featured prominently on their home page—because there is no more important question in the coronavirus crisis right now than how to get off the path led by Italy and onto the track of countries like Singapore.

As the Financial Times notes, most Western countries are seeing growth in Covid-19 cases that resembles the exponential curve taken first by Italy, followed closely by Spain and France.

This is very bad news, since Italy’s hospital system has run out of hospital space and particularly intensive care beds, forcing medical centers to turn away patients in need of critical care (PBS, 3/13/20). As journalist Mattia Ferraresi of the Italian paper Il Foglio wrote in the Boston Globe (3/13/20):

What has happened in Italy shows that less-than-urgent appeals to the public by the government to slightly change habits regarding social interactions aren’t enough when the terrible outcomes they are designed to prevent are not yet apparent; when they become evident, it’s generally too late to act….

The way to avoid or mitigate all this in the United States and elsewhere is to do something similar to what Italy, Denmark, and Finland are doing now, but without wasting the few, messy weeks in which we thought a few local lockdowns, canceling public gatherings, and warmly encouraging working from home would be enough stop the spread of the virus. We now know that wasn’t nearly enough…..

Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte announced the latest step in a process that has progressively turned Italy into a fully quarantined country. Shops are mandated to be closed at all times, with the exception of pharmacies, food stores, and newsstands, as the government wisely considers information a primary need. All non-essential jobs have been temporarily stopped.

The good news is that there are some countries that seem to be meeting the coronavirus challenge successfully. In addition to Singapore, Hong Kong and possibly Japan, highlighted on the chart, Taiwan and Vietnam also appear to have contained the epidemic despite their proximity to the pandemic’s epicenter.

Perhaps most significantly, China, where the outbreak was first seen, with Covid-19 widespread in the city of Wuhan and the surrounding province of Hubei, appears to have brought the epidemic under control. Al Jazeera (3/17/20) reports:

Across the country, 13 out of 34 provinces in China have cleared their remaining cases, and approximately 69,000 of 81,000 confirmed cases have been discharged.

Even in Hubei, where some 10,000 cases remain, the pressure on front-line medical workers has eased. On March 17, the first batch of nearly 4,000 medical workers who were parachuted into Wuhan to help control the outbreak were able to leave.

With so many provinces having downgraded their emergency response levels, China is slowly—and cautiously—returning to normal life.

Classes are gradually resuming after most students spent the last month or so at home and studying online. In provinces classified as “low risk of infection,” including Guizhou, Qinghai, Tibet and Xinjiang, local governments have allowed educational institutions to resume classes this month.

(While people are appropriately skeptical of China’s official numbers, the virus’s tendency to exponential growth leaves little room for a coverup; if China were trying to hide an uncontrolled epidemic, its watchful neighbors would quickly spot the deceit.)

So how are US media handling the vital task of informing the public on how to avoid becoming like Italy and achieve the apparent success of China? Not well, unfortunately. A widely shared feature in the Washington Post (3/14/20), “Why Outbreaks Like Coronavirus Spread Exponentially, and How to ‘Flatten the Curve,’” illustrates the problem. The piece, which purports to illustrate the principles of epidemiology with an animated virtual disease called “simulitis,” offers the Chinese experience as an example of what not to do:

To slow simulitis, let’s try to create a forced quarantine, such as the one the Chinese government imposed on Hubei province, covid-19’s ground zero.

Whoops! As health experts would expect, it proved impossible to completely seal off the sick population from the healthy.

Leana Wen, the former health commissioner for the city of Baltimore, explained the impracticalities of forced quarantines to the Washington Post in January. “Many people work in the city and live in neighboring counties, and vice versa,“ Wen said. “Would people be separated from their families? How would every road be blocked? How would supplies reach residents?”

As Lawrence O. Gostin, a professor of global health law at Georgetown University, put it: “The truth is those kinds of lockdowns are very rare and never effective.”

This is on March 14, when in the real world China had used this “never effective” technique to bring new Covid-19 cases down to 20 a day—from a peak of perhaps 5,000 a day—and deaths from 150 down to 10 a day, while people in Hubei continued to eat. What does the Post‘s “simulitis” tell us we should do instead?

Fortunately, there are other ways to slow an outbreak. Above all, health officials have encouraged people to avoid public gatherings, to stay home more often and to keep their distance from others. If people are less mobile and interact with each other less, the virus has fewer opportunities to spread.

In other words, the kind of “less-than-urgent appeals to the public by the government to slightly change habits regarding social interactions” that, as Il Foglio‘s Ferrasi had pointed out in the Boston Globe the day before, had already proved utterly ineffective in Italy, leading to a situation where

doctors were being forced to start making difficult triage decisions, admitting people who desperately need mechanical ventilation based on age, life expectancy, and other factors…. Some of the people who can’t get medical care are dying in their homes.

This reckless disregard for the real-world lessons being taught by the virus was by no means confined to the Post. The New York Times, which early on in the pandemic mocked the Chinese lockdown as “Mao-style social control” (2/15/20), ran a piece (3/13/20) dismissing the Chinese example:

Lockdowns and forced quarantines on this scale or the nature of some methods—like the collection of mobile phone location data and facial recognition technology to track people’s movements—cannot readily be replicated in other countries, especially democratic ones with institutional protections for individual rights.

The idea that China, unlike the US, engages in high-tech surveillance of its people is a common self-flattering trope in US media (FAIR.org, 7/10/18). But more problematic is the rejection of the tools China used to stamp out an ongoing outbreak in favor of the techniques that Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore used to prevent ones from getting started—notably, Italian-style efforts to “generally suppress silent transmission in the community by reducing contact between individuals (self-isolation, social distancing, heightened hygiene).”

Most recently, the Times (3/16/20) published an article that focused on the results of a simulation by researchers at Imperial College London, which they said found that “to curb the epidemic, there would need to be drastic restrictions on work, school and social gatherings for periods of time until a vaccine was available, which could take 18 months.” A look at the actual report (3/16/20) shows that the measures contemplated by the British group were in actuality far less “drastic” than those that have been successfully implemented in China. What the report proposed was a

combination of social distancing of the entire population, home isolation of cases and household quarantine of their family members. This may need to be supplemented by school and university closures.

This program is far less sweeping than the restrictions already implemented in the Times‘ own New York City, where not only schools but restaurants, bars, cinemas and gyms and have been ordered closed, let alone than the general lockdown on all nonessential activity imposed in Hubei—as well as in Italy, Spain and France as desperate measures in the face of collapsing health systems. It’s no wonder that the British simulation found that such insufficient interventions would have to be continued until a vaccine saves us—but why not consider the effects of the approaches already being taken in the real world, where roughly a month and a half passed between the declaration of a lockdown in Wuhan and the announcement that the outbreak had been contained on March 10?

For too long, truly comprehensive measures against the coronavirus have been treated as off the table. When the infected Grand Princess cruise ship was allowed to dock in Oakland, the Los Angeles Times (3/8/20) ran a piece headlined “‘We’re Past the Point of Containment’: Coronavirus Fight Enters New Phase.” That new phase was “mitigation,” since “containment is no longer possible,” and it meant that communities would

need to start thinking about whether it makes sense to cancel large gatherings, close schools and make it more feasible for employees to work from home.

The idea that the best one could hope for is to slow, not stop, the spread of the coronavirus leads to the advice to “flatten the curve” of the peak of infections, as featured in the Washington Post feature and elsewhere (including a FAIR.org post—3/10/20). The idea is that measures like social distancing and washing one’s hands can lower the rate of infection, spreading cases out enough to keep the healthcare system from collapsing.

But as the AI Foundation’s Joscha Bach pointed out in a piece for Medium (3/13/20), the idea that it’s possible to flatten the curve enough to prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed is a dangerous misconception: The coronavirus has a lengthy incubation period (averaging five days, but sometimes as long as 14 days), can be transmitted asymptomatically, and often requires hospitalization and intensive care (roughly 20% and 6% of patients, respectively). If the disease is allowed to spread until it’s naturally halted by herd immunity—which is what the “flatten the curve” model presumes—this would mean (assuming a final infection rate of 40%) that more than 20 million Americans would need to be hospitalized, and more than 4 million would require intensive care (Health Affairs, 3/17/20)…in a country with less than a million hospital beds and less than 70,000 adult intensive care beds. There is no feasible way to redistribute these cases enough to prevent a total swamping of our hospital capacity.

Covid-19 also has a substantial mortality rate. A Lancet article (3/12/20) suggested that it could be as high as 5.7%; an article in Emerging Infectious Diseases (6/20) suggests a lower figure, perhaps 0.9%, might be more likely—though it could be in higher in “high-income countries with limited surge capacity in hospital services because elevated case-fatality risks could be seen at the peak of local epidemics.” But even the more conservative figure, coupled with the 40% infection rate possible with a “flatten the curve” strategy, projects more than a million deaths in the United States, before taking into account the lethal effects of hospital overload.

It’s hard to escape the impression that “flattening the curve” has been offered as a solution because any strategy that aimed at actually stopping the spread of the virus would necessarily have a ruinous economic impact. China’s economy has been “devastated” by the anti-coronavirus drive (CNN, 3/16/20)—though it will no doubt turn out to be doing quite well in comparison with countries that had to impose nationwide lockdowns after acting too late. The price of not stopping the coronavirus, it turns out, is too great for any nation to pay; that’s the lesson the real world is teaching us, and one we have to heed.