Media is important now.

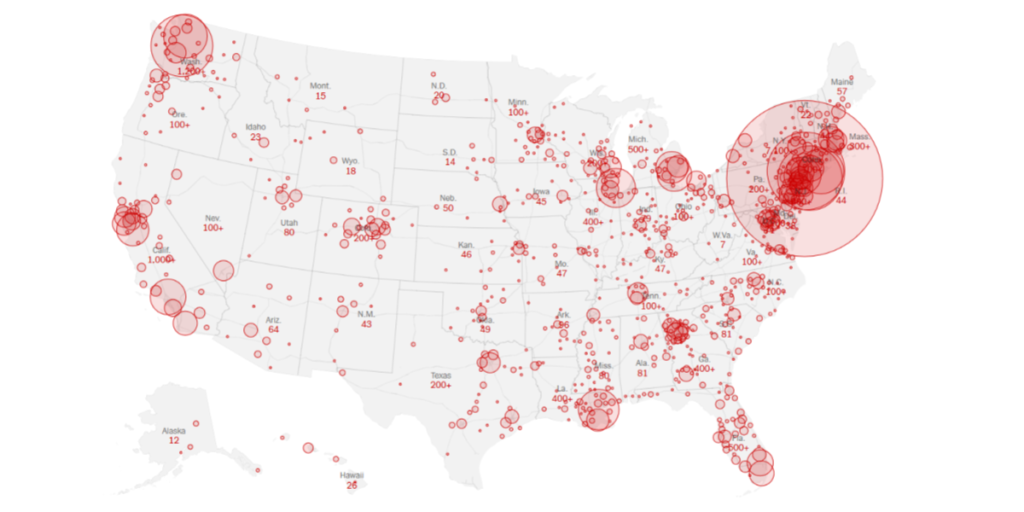

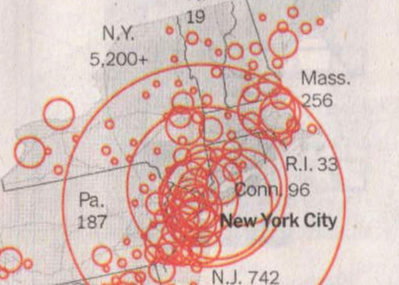

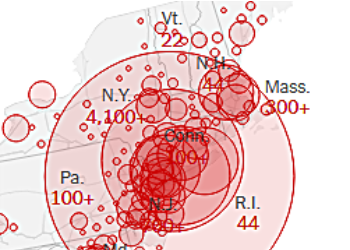

The front page of the New York Times (late) print edition for March 20, 2020, bore a large map of the United States, illustrating reported cases of Covid-19 by state and county, as of March 19, 4 p.m. EDT. Readers in the paper’s home city might have been particularly interested in the count for the state of New York—which, according to the map, was up to 5,200+ cases:

Curiously, the morning that paper was delivered, the online version of the map, with the supposedly latest figures, had cases in New York State at 4,100+—1,100 fewer, a reduction of almost 20%—with no explanation for the discrepancy. (Illustrating the exponential growth of the outbreak, by the afternoon of March 20, the online map had 7,100+ cases for New York State.)

A less excusable example of an influential media voice failing to get the story straight was Jennifer Rubin‘s March 18 Washington Post column, which rightfully lambasted President Donald Trump for fatally bungling the response to the pandemic. But in that column, Rubin did her own bungling, writing:

Trump did not show any real recognition of the magnitude of the problem until his administration got hold of a study from Britain. “The Imperial College London group reported that if nothing was done by governments and individuals and the pandemic remained uncontrolled, 510,000 would die in Britain and 2.2 million in the United States over the course of the outbreak,” the Post reports. Even if we now institute uniform, serious measures to mitigate the spread of the virus, we would “reduce mortality by half, to 260,000 people in the United Kingdom and 1.1 million in the United States.”

By Rubin’s account, we’re doomed to a seven-figure casualty toll, no matter what we do. But that is not what the Post news article she’s citing said. Immediately after the passage she quotes—but interrupted by a photograph—the story continues:

Finally, if the British government quickly went all-out to suppress viral spread — aiming to reverse epidemic growth and reduce the case load to a low level — then the number of dead in the country could drop to below 20,000. To do this, the researchers said, Britain would have to enforce social distancing for the entire population, isolate all cases, demand quarantines of entire households where anyone is sick, and close all schools and universities — and do this not for weeks but for 12 to 18 months, until a vaccine is available.

From 260,000 to 20,000 is, obviously, a substantial drop; if the same reduction in deaths is envisioned for the United States, that would bring the toll down below 85,000. To exaggerate the cost in human lives of what your source offers as the best-case scenario by 1,200% is simply irresponsible.

And it should be recognized that her source, the Washington Post news article by William Booth (3/17/20), itself misrepresents the Imperial College study in a crucial way. It did not envision the government going “all-out to suppress viral spread”; you’ll note that its description of proposed actions does not include banning large public gatherings, or shutting down public spaces like restaurants, bars, cinemas and theaters, as New York City announced it would do on March 15. And it certainly does not contemplate all nonessential employees staying home, as one in five Americans had been told to do by March 20. (See FAIR.org, 3/17/20.)

Could these more strenuous interventions reduce the death toll below 85,000? Could they bring hope for a return to a semblance of normalcy sooner than a year or 18 months? It seems likely, but the Post report suggested that the comparatively modest restrictions modeled by the Imperial College are the best we can do.

Given that this study seems to have a profound impact on official crisis planning on both sides of the Atlantic, journalists seem to have had considerable trouble reading and comprehending what it is and isn’t saying. A New York Times article (3/17/20) devoted to the report, by Mark Landler and Stephen Castle, described the relatively gentle virus-fighting steps modeled by the Imperial College as “radical lockdown policies” and “far stricter lockdowns,” though they don’t envision locking down anyone. They were far less sweeping than the shelter-in-place order that had been issued for seven Bay Area counties the day before (Mercury News, 3/16/20).

It is crucial that the public understand that what seems to be the single-most important document guiding official decision-making, and the source for the dismaying projection that coronavirus-related restrictions may have to remain in place as long as 18 months, depends on the unstated assumption that the most vigorous actions taken to fight the epidemic have to allow business to continue as close to usual as possible. In this, the Imperial College, which as its name suggests is very close to the British government, appears to be guided by the same philosophy that informs a remarkable Wall Street Journal editorial (3/19/20):

This won’t be popular to read in some quarters, but federal and state officials need to start adjusting their anti-virus strategy now to avoid an economic recession that will dwarf the harm from 2008–2009…. Barring [a quick vaccine], our leaders and our society will very soon need to shift their virus-fighting strategy to something that is sustainable…. America urgently needs a pandemic strategy that is more economically and socially sustainable than the current national lockdown.

In other words, saving lives is all well and good, but we’ve got businesses to run. If that’s the attitude behind the report that underlies the thinking of top US and British officials, citizens need to know that—and they won’t learn it from inaccurate reporting.