Once again the media failed and at times allowed a false narrative to take hold with some Americans. Did the Sweden media dereliction help fuel the Right’s buffoonery?

by Neil deMause

Last week, a piece of news put another dent in the Swedish government’s claims that it’s been able to get Covid-19 under control without stay-at-home orders.

Swedish officials had previously said that their capital city of Stockholm could be approaching “herd immunity,” where so many people had contracted and survived the virus that their natural resistance could make the coronavirus begin to disappear on its own (CNBC, 4/22/20). But testing in Stockholm found that, in fact, only 7.3% of residents had SARS-COV-2 antibodies (Guardian, 5/21/20; CNN, 5/21/20). Swedish state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell called the figure “a bit lower than we’d thought.”

That wasn’t the only curiously low number in the media coverage of the latest findings, though. The Guardian noted that the Swedish government “had previously said it expected about 25% [of Stockholm residents] to have been infected by 1 May.” But even that level of infection wouldn’t have been nearly enough to approach any significant herd immunity—while the exact threshold varies depending on precisely how contagious a virus turns out to be, best estimates for the coronavirus that causes Covid-19 run from 70% to 82%. (It’s estimated that the coronavirus infected 69% of the population of the Italian province of Bergamo by early May, despite a belated lockdown.) So even before the latest test results, the Swedish government’s claim of nearing herd immunity turns out to have been a fraud.

None of this, alarmingly, stopped the international press from initially touting Sweden’s claims that herd immunity was a potentially promising way to avoid widespread lockdowns.

CNBC (4/22/20) called the nation’s approach “controversial,” but quoted Tegnell uncritically as saying 20% of Stockholm’s population “is already immune to the virus” and “in a few weeks’ time we might reach herd immunity.” NPR (4/26/20) cited Swedish ambassador to the U.S. Karin Ulrika Olofsdotter as providing similar figures, except Olofsdotter floated 30% as the number already immune. USA Today (4/28/20) then ran a long interview with Tegnell in which he guesstimated 25% exposure in Stockholm, with herd immunity arriving “within a matter of weeks”—a policy it noted scientists in Sweden and abroad had termed “dangerous,” but which “is broadly supported by most Swedes.”

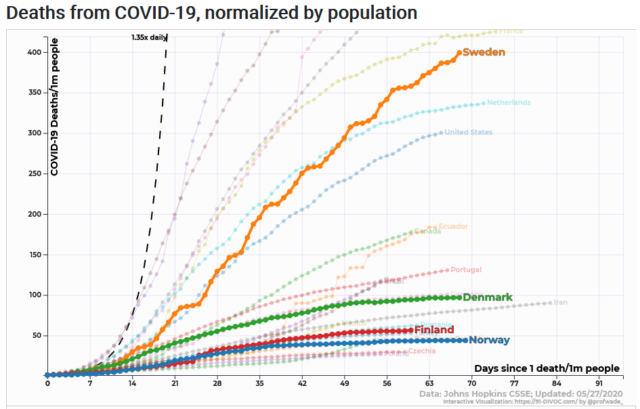

None of these outlets questioned Swedish officials on their claims, or sought out comment from infectious disease experts. (Tegnell himself is an epidemiologist; his predecessor, Annika Linde, told the Observer—5/24/20—that she now believed that Sweden should have shut down more completely and earlier to reduce the spread of Covid-19.) In the USA Today report, Tegnell cited a study of hospital workers in Stockholm that found 27% were coronavirus positive, then asserted without attribution that this should be seen as representative of the general population, because “most of those are immune from transmission in society, not the workplace,” even though healthcare workers have been testing positive at far higher rates than average residents in multiple nations (Associated Press, 4/14/20). And no reporters stopped to wonder how on earth Stockholm’s infection rates could double or triple in a matter of weeks without a massive death toll—even at the low-end estimate infection fatality rate of 0.56% based on a study in Italy, an additional 40% of Stockholm’s population becoming infected would result in more than 2,000 added deaths in that city alone, which would move Sweden from the sixth-highest to the third-highest per capita death toll in the world.

This is especially important as “herd immunity” has become a popular stalking horse among certain right-wingers seeking to argue that infecting broad swathes of the population is the best way to return the world — and the world economy — to normal. The Federalist (3/25/20) ran an article advocating for “chickenpox parties” to infect as many young, healthy people as possible, so those who recover could “move freely, work anywhere and be freed from social distancing,” an edit that the article’s author, an Oregon dermatologist and internist, ended up disowning, while Twitter briefly suspended the Federalist‘s account for “misinformation” until its tweet about the article was removed (Willamette Week, 3/26/20).

Boris Johnson’s British government briefly insisted that it could achieve herd immunity by slowing the onset of infections without stopping them, before swiftly backing off that plan in favor of stay-at-home orders (Atlantic, 3/16/20). And when Rush Limbaugh (4/10/20) declared approvingly that “I believe herd immunity has occurred in California,” and that “in parts of this country, we could reopen,” two Johns Hopkins epidemiologists issued a response noting that herd immunity will not be achieved in 2020 “barring a public health catastrophe.”

Still, the herd immunity argument continues to spread. Republican US Rep. Ted Yoho of Florida recently cited herd immunity as a reason he saw no need to wear a mask in public (CNN, 5/15/20); and a widely disseminated AP photo pictured a protester against Minnesota’s stay-at-home policy holding a sign reading “Be Like Sweden” (San Jose Mercury News, 4/18/20), something that was doubtless inspired by articles in the conservative press advocating letting people contract the virus in order to force the pandemic to burn out (National Review, 4/6/20).

The argument by herd-immunity advocates is that the virus can safely be allowed to spread in the non-high-risk population, while only the elderly or those with preexisting conditions are isolated. (They tend to downplay such details as the fact that just one risk factor for Covid deaths, hypertension, affects nearly half of all US adults.) The National Review argued, for example, that “the current COVID-19 death rate in Sweden (40 deaths per million of population) is substantially lower than the Swedish death rate in a normal flu season.”

The explanation, it turns out, is less herd immunity than a limited spread of the virus into the Swedish population: Assuming a 0.56% fatality rate, Sweden’s 4,029 total Covid-19 deaths as of May 26 would suggest that about 7% of the Swedish population has been infected, right in line with the latest antibody survey.

If one major city can lay claim to having gotten the closest to herd immunity, it’s New York City, with nearly one in five residents testing positive for antibodies by the end of April, and more than two in five in some low-income neighborhoods with high numbers of service workers and families living in close quarters. But that still isn’t anywhere near even the minimum herd immunity level of 70%; at a 0.56% fatality rate, New York City would need to suffer an additional 23,500 deaths—more than twice as many as it has already endured—before the virus would begin to burn out on its own. (If the New York City fatality rate is more like 1.2%—as the highest estimates of Covid-19 deaths in the city, plus a 20% infection rate, would imply—then at minimum, herd immunity would require 50,000 new deaths.)

Meanwhile, even if Sweden’s bogus herd immunity success weren’t inspiring would-be copycats, it would still be yet another sign of the worrying media trend of citing government officials on anti-Covid-19 measures without checking that their statements make any scientific sense. Much of pandemic coverage has already relied heavily on the statements of elected officials without sufficient factchecking (FAIR.org, 3/12/20), whether those misstatements came from Donald Trump or New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (FAIR, 5/9/20); it’s significant that NPR (5/25/20) finally corrected its initial rosy reporting on Sweden and herd immunity only when Tegnell himself admitted that the numbers weren’t working out.

If media outlets are going to help chart a course out of this pandemic, they need to start investigating whether government claims make sense at the time they’re made, not just after elected officials walk them back. If they can’t do that job, we could be in for a very long haul.