A hundred and eleven years ago, a ship considered to be “unsinkable” fell to the bottom of the ocean after hitting an iceberg. More than a thousand people died as the Titanic sank into the icy waters of the Atlantic Ocean, among them the engineer who had warned against cutting corners and safety standards.

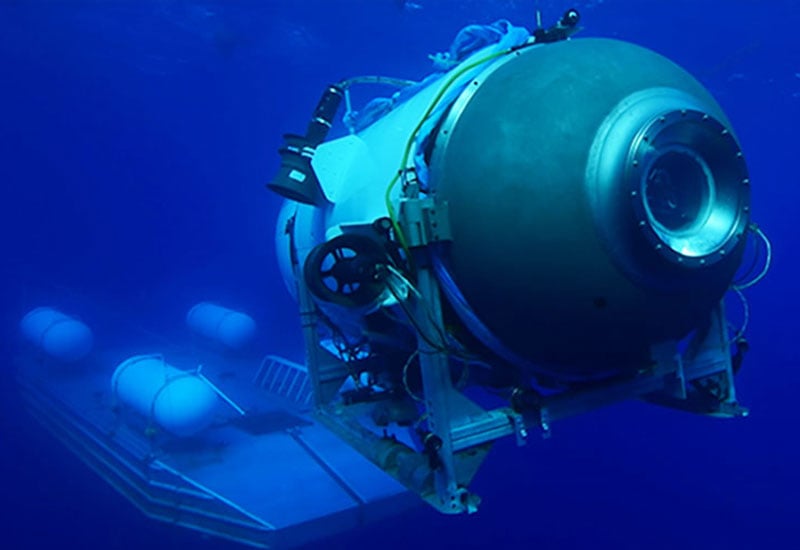

The parallels between the Titanic and the Titan—the tiny headline-garnering submersible that was lost while trying to view the sunken ship’s remains—would be laughably striking were it not for the fact that lives were lost.

Whereas the White Star Line company was focused on building luxury liners for the very wealthy, OceanGate, the company that owned the doomed submersible, runs a marine tourism business for people willing to pay $250,000 to dive more than 12,000 feet into the ocean inside a cramped tube to see the ruins of the Titanic.

There appears to be no end to the irony linking the Titanic to the Titan. OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush, who was piloting the submersible and is presumed dead along with his four passengers, once boasted about “breaking rules” to engineer a craft made of carbon fiber instead of steel to withstand the pressures of the deep ocean. According to the New York Times, his wife Wendy, “is a great-great-granddaughter of the retailing magnate Isidor Straus and his wife, Ida, two of the wealthiest people to die aboard the [Titanic] ocean liner.”

Hindsight is 20-20. The Titanic’s appeal endures in part because it offered a lesson in capitalist hubris as a ship deemed “unsinkable” sank on its maiden voyage in spite of warnings about safety standards. It also offered a stark lesson in how the wealthy were privileged over the poor before and during evacuation. But the Titan story suggests our values have not changed since 1912.

Like the Titanic, the Titan faced criticism over safety standards. In 2018, OceanGate’s own director of marine operations, David Lochridge warned of “potential dangers to passengers of the Titan.” That same year, several experts with the Marine Technology Society signed onto a letter warning Rush of potentially “catastrophic” consequences for forgoing safety certifications.

In a 2019 press release, OceanGate countered such criticisms saying, “Bringing an outside entity up to speed on every innovation before it is put into real-world testing is anathema to rapid innovation.” Just as the Titanic’s owners eschewed some safety standards in their eagerness to sell tickets to high-paying customers, the OceanGate CEO made it clear that he felt he was above the laws of physics. “At some point, safety just is pure waste,” he said a year before his death. Ouch.

Experts now believe it was Rush’s reliance on carbon fiber that likely caused the Titan to implode. Rapid innovation can cause rapid death.

The fate of the Titan also offers a warning against the arrogance of thrill-seeking billionaires. The “extreme tourism” industry has skyrocketed since the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions were eased. One of the five men who died on the Titan, Hamish Harding, a British billionaire based in Dubai, UAE, had a penchant for dangerous and expensive exploration and boasted recognition by the Guinness World Records Book. Just a year before he boarded the Titan to dive more than ten thousand feet below the ocean surface, he flew into space on board Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s vanity project, Blue Origin.

“What I’ve seen with the ultra-rich—money is no object when it comes to experiences,” remarked a public relations specialist to CNN. “They want something they’ll never forget.”

While the Guinness World Records eulogized the late Harding with words like “adventuring,” “pioneering,” and “entrepreneurial,” according to Newsweek, the type of extreme tourism that Harding and others like him are drawn to “can threaten the environment or lead to exorbitant rescue missions and, rarely and most recently, tragedy.”

Indeed, a massive amount of publicly funded infrastructure was mobilized in a days-long rescue operation for the doomed Titan before it was known that the submersible had imploded, killing everyone on board.

U.S. Coast Guard Rear Admiral John Mauger told CNN, “Teams were able to mobilize an immense amount of gear to the site in just really a remarkable amount of time… given the fact that we started without any sort of vessel response plan for this or any sort of pre-staged resources.” In response to a call for help from the U.S. Navy, even the French government sent a ship to help.

News stories breathlessly shared details of what it would be like to be lost in the deep sea inside a claustrophobically small metal tube floating in the ocean’s abyss, piloted only by a video game console. We were called upon to personally feel the pain of the wealthy explorers.

But there was little public discussion of the disaster that took place only a week before the Titan went missing when hundreds of migrants heading from Libya to Italy were presumed dead after their boat sank in the Mediterranean Sea. Writing for NBC, reporter Chantal Da Silva wrote one of the very few stories on what is likely to be among the worst such disasters in recent history and rightfully compared it to the response garnered by the Titan. She quoted Human Rights Watch’s Judith Sunderland, saying, “It’s a horrifying and disgusting contrast,” to see the difference in resources being mobilized for the Titan versus a boat of hundreds of desperate refugees. Sunderland added, “The willingness to allow certain people to die while every effort is made to save others… it’s a… really dark reflection on humanity.”

The Titan is what you get when a corporate cost-cutting mindset meets the lavish thrill-seeking, money-is-no-object ethos of billionaires—the same sort of people who espouse cost-cutting in the interest of profits. In his 1955 bestselling book about the Titanic, A Night to Remember, Walter Lord wrote, “The Titanic woke them up. Never again would they be quite so sure of themselves. In technology especially, the disaster was a terrible blow.” Will the Titan’s fate be a lesson to the so-called “innovators” who scoff at safety regulations as a waste of time?

Lord also wrote of the Titanic, “If this supreme achievement was so terribly fragile, what about everything else? If wealth meant so little on this cold April night, did it mean so much the rest of the year?” As the bodies of migrants whose names we will never know remain lost at sea, we are reminded that just like the billionaires who care more for the state of a rotting shipwreck than of humans fleeing violence, war, and poverty, our own collective values have been perverted to uplift elites over others. Will society rethink its faith in moneyed heroes?

As broken bits of the submersible lie on the ocean floor next to the equally doomed Titanic, when will we learn from the lessons in hubris offered by such disasters?

Author Bio: Sonali Kolhatkar is an award-winning multimedia journalist. She is the founder, host, and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a weekly television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. Her forthcoming book is Rising Up: The Power of Narrative in Pursuing Racial Justice (City Lights Books, 2023). She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and the racial justice and civil liberties editor at Yes! Magazine. She serves as the co-director of the nonprofit solidarity organization the Afghan Women’s Mission and is a co-author of Bleeding Afghanistan. She also sits on the board of directors of Justice Action Center, an immigrant rights organization.

Source: Independent Media Institute

Credit Line: This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute.