The Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center’s (MassBudget) annual Labor Day report came out with some striking minimum wage results. It turns out most progressives were right all along. States that raised the minimum wage saw much larger low-wage earnings gains than states that did not raise wages. This undermines a common right-wing media myth that higher wages reduce worker earnings.

Following is the introduction of the report which provides a synopsis of the entire analysis. The entire report can be read here.

2016 State of Working Massachusetts

For the majority of working people, hourly wages and yearly incomes share a close link; with hourly wages being the principal source of their income. While wages have finally begun to grow again for most workers in the past year, at both the national and state levels wage growth for the majority of workers has been disappointing for more than 30 years.

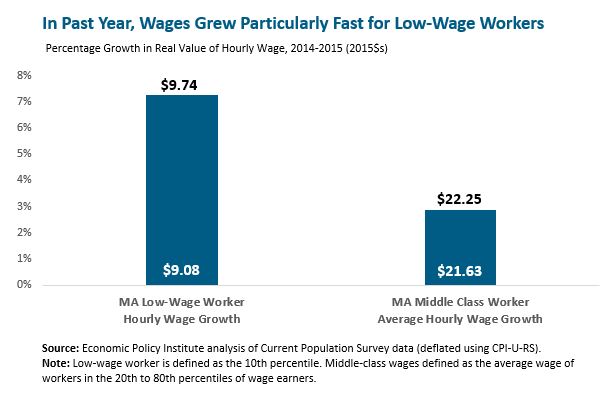

During this past year, average wages for the broad middle class rose almost 3 percent ($21.63 an hour to $22.25 an hour, adjusted for inflation).1While this is good growth, our lowest wage workers, who benefitted from the state minimum wage increase in 2014, have seen even stronger progress, with an increase of over 7 percent over the past year ($9.08 an hour to $9.74 an hour, adjusted for inflation). This wage growth is aligned with other positive trends in our state including steady job growth, and declines in unemployment and child poverty. And while this is a positive sign, this strong real growth was partly due to inflation being almost zero, so virtually all nominal wage growth shows up as real wage growth–and this uncharacteristically low inflation is a trend that is unlikely to continue.

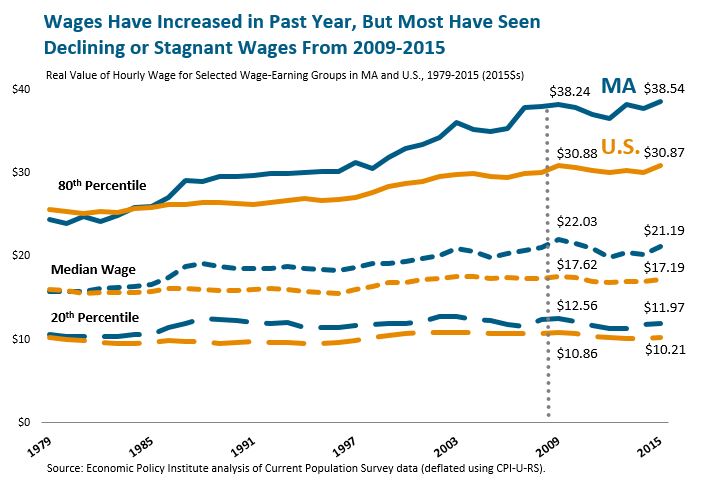

While changes over the past year have been promising, a look at the recent Great Recession and the subsequent recovery (2009-2015)2 paints a dimmer story: wages actually have declined slightly or have remained stagnant for low and middle wage earners during this period. Though wages have started to climb in 2015, they are still below 2009 levels for all but our highest wage workers. While Massachusetts workers have fared better than U.S. workers over the past several decades, poor wage growth has been a defining characteristic of our economy.

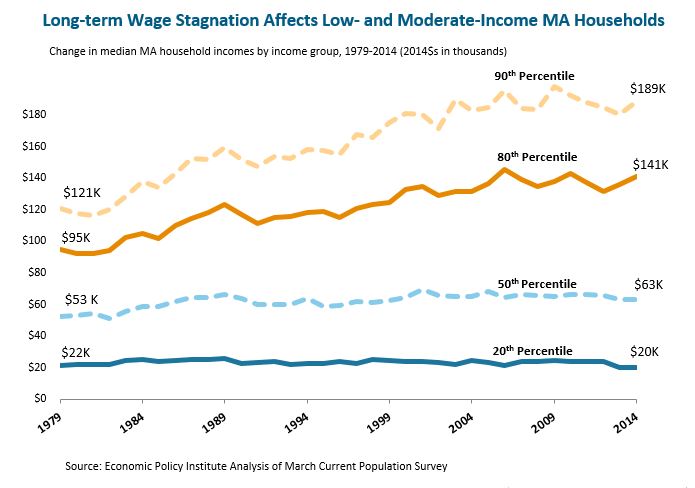

Not surprisingly, the wage stagnation of the last three decades has translated into similarly poor income growth for most Massachusetts households (see chart, below). Low-income households have suffered actual income declines since the late 1970s. Insufficient incomes create real and substantial problems for many workers and their families, negatively impacting their quality of life, limiting their own economic opportunities, and the opportunities they can provide for their children.

Wage-driven income stagnation is also a core cause of the growth of extreme income inequality.3 And we see both nationally and here in Massachusetts, a pattern where the top 1 percent of households, between 2009 and 2013, received the overwhelming majority of all income growth.4 Such extreme income inequality, in turn, threatens the long-term strength of our economy.5 As a key driver of all these problems (working people struggling to make ends meet, extreme income inequality, a less vital economy), wage stagnation stands as one of, if not the central economic challenge of our day.

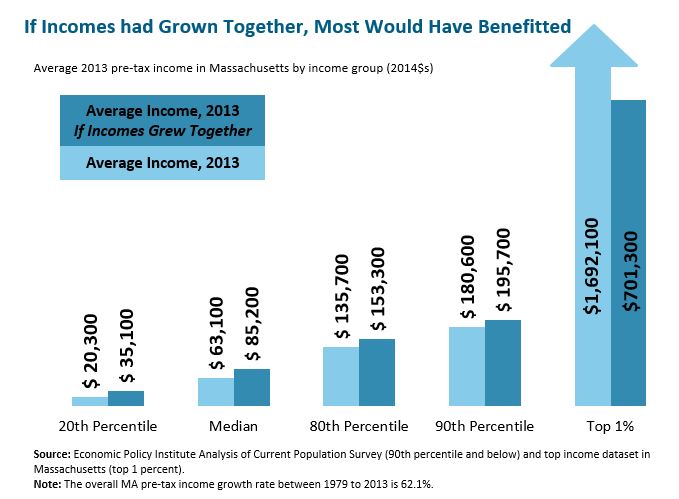

Indeed, if economic growth over the past three decades had translated into proportionate income growth for low, middle, and high income households—rather than disproportionally benefitting the highest income households—then 90 percent of Massachusetts households would have substantially higher incomes today (see chart, below). Median household income would have been about $22,000 higher in 2013 and households in the bottom 20 percent would have seen about $15,000 more in annual income. Even those in the 80th and 90th percentile of income earners would have seen a substantial boost ($17,600 and $15,100, respectively). For many low and moderate income families, this amount of additional annual income could transform their day-to-day lives and their possibilities for the future.

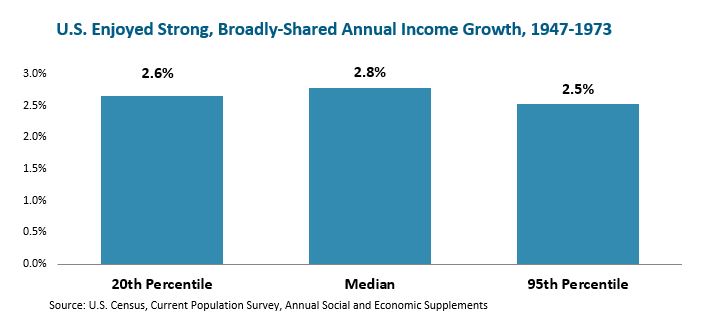

The trend of recent decades—where a disproportionate amount of the benefits of economic growth have gone to the highest income households—has not been a permanent feature of the American economy. In fact, in the three decades following WWII, strong overall income growth was matched with—and in part, likely was the product of—far moreequitable income growth.6 During this post-war period, high, middle, and lower income households all enjoyed significant annual income gains (see chart, below).

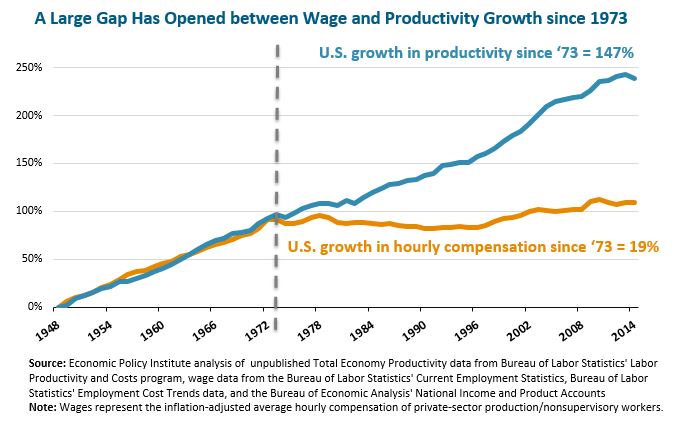

During this post-WWII period, notably, wages also grew in lockstep with the overall growth in productivity (see chart, below). As workers delivered more and better products during each hour of their work day, their pay for each hour increased. In the 1970s, however, this pattern began to change: productivity continued its steady rise, but wages for average workers stagnated (see chart, below).

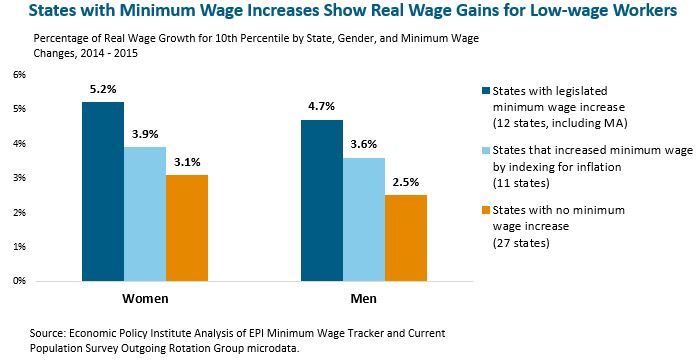

Reconnecting wage growth to gains in productivity—in other words, making sure that when productivity increases, the new value being created leads to higher wages as well as profits—is a core challenge for today’s policy makers, at both the federal and state levels. Massachusetts already has taken a modest but important step toward achieving this goal by adopting a state minimum wage of $11 an hour by 2017. Massachusetts is accompanied by a handful of states such as California, New York, Vermont, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and others that have passed legislation in the past two years that would increase their minimum wage.7 In 2015, low-wage workers in our Commonwealth and in other states with recent minimum wage increases have seen real wage growth. The chart below shows that the growth in wages for the bottom 10th percentile of earners was fastest in states with legislated increases (versus minimum wage increases through indexing to inflation or no increase at all). This was true for both men and women, however, women’s wages grew even more than men’s among low wage workers. Nevertheless, poor wage growth and low incomes remain a deeply problematic reality for too many Massachusetts workers and their families. Furthermore, there continues to be a wage gap on the state level, and nationally, based on gender and race. By reconnecting all workers’ wages to the ever-growing productive capacity of our economy, however, we can move ourselves toward a future of broadly shared prosperity.

Commonsense policy changes can, in fact, markedly lift workers’ wages. When the minimum wage rose in our state from $8 to $9 an hour in 2015—wages grew significantly for the lowest income 10th percent of workers (7.3 percent) as compared to the more moderate rise the state’s middle class workers saw of 2.9 percent. This rise in average, broad middle class wages was faster in Massachusetts than in most other states.

Wages for the broad middle class (those in the 20th to 80th percentiles of income) grew about 3 percent in 2015, after accounting for inflation. If that rate of real growth could be sustained it would lead to meaningful improvements in the standard of living of working people. There are reasons to be concerned, however, that this rate of growth was a bit of an anomaly. Inflation was very low (0.1%) in 2015, so virtually all wage growth showed up as real wage growth. The problem is that if inflation returns to a more normal level next year (say, for example, 2 percent) then real wage growth will slow, unless nominal wage growth accelerates 5 percent (the current growth of 3 percent plus 2 percent inflation), which is unlikely. Focusing on real wage growth makes sense since what matters to a worker is how much more she can buy each year.

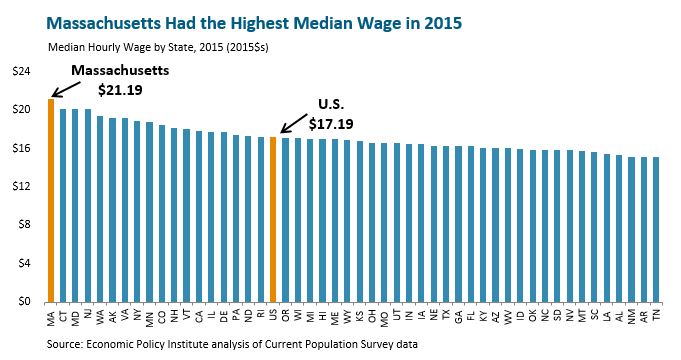

Another bright spot for Massachusetts is that we have the highest median wage in the nation (see chart, below). This relatively high median wage is directly connected to the high levels of education of many Massachusetts workers. (To read more about the connection between education and wages, see the Education and the Economy section of this report.)

It will not be good for Massachusetts working families if the next thirty years look like the last thirty. There are, however, some hopeful signs. An improving national labor market, with falling unemployment and more job opportunities—which we’ve seen indications of here in Massachusetts over the last few quarters (see the Jobs & Employment section of this report)—can help to push up wages and incomes over the long-term. Massachusetts also recently adopted an earned paid sick time law that makes it possible for everyone who works in Massachusetts to be able to take a limited amount of time off when needed to care for a sick child, or parent, or if the employee is too sick to work. There are other steps that Massachusetts could take as well, such as adopting a Paid Family and Medical Leave law, to help working parents meet the challenges of balancing work and family obligations.

Indeed, tighter nationwide labor markets are critical to creating the conditions under which workers are more likely to see an increase in their wages. Massachusetts cannot simply sit back and wait for workers’ economic conditions to improve on their own. Policy choices have played a major role in producing the wage and income stagnation that has characterized the last three decades. Therefore, federal and state policy choices will need to continue being part of the solution.

Viewers are encouraged to subscribe and join the conversation for more insightful commentary and to support progressive messages. Together, we can populate the internet with progressive messages that represent the true aspirations of most Americans.