by Lauren Angel

Lauren Angel is a Ph.D. candidate in twentieth-century American history at the George Washington University. An AAUW American Dissertation Fellow, Lauren’s current research has also been funded by a Cosmos Scholars Grant and a New York Public Library Research Fellowship.

When an anonymous right-wing twitter account released a video of incoming congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez dancing in a joyful homage to The Breakfast Club, commentators on both sides of the aisle were quick to react. Pundits debated the optics of combining dance and politics, questioning whether Ocasio-Cortez’s gender has shaped our expectations of how she ought to behave. But while many in the media celebrated the sight of a youthful Ocasio-Cortez and her Boston University pals dancing together, missing from these conversations was an appreciation of the role that dancing bodies have long played in American political life.

Physical appearance and bodily movements have traditionally been tied to expressions of personal identity. Dressing in a certain way and following certain behavioral norms have historically marked people as belonging to specific social categories, categories determined by social constructions of race and gender. Because the act of dancing is fundamentally tied to behavior and appearance, debates about dance have inspired lengthy discussions regarding representations of race, gender, and even American national identity. From Victorian-era ideas about dance and demeanor, to folk dances meant to help assimilate newly-arrived U.S. immigrants, fears that public dance halls would lead to white slavery, and the uses of concert dance as cultural weapon in the Cold War, the act of dancing has helped to define American social and political issues for centuries.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, dancing was an important part of a young person’s introduction to polite society. As one guidebook recounted, in the words of John Locke, children “should be taught to dance as soon as they are capable of learning it; for … it gives children manly thoughts and carriage more than anything.” Victorian sensibilities held that the body and its movements demonstrated cultural refinement and could even reveal someone’s moral fiber. However, although physical grace was important for both men and women, there were also key differences in the gendered implications of this attribute.

According to the wisdom of the day, young men who studied fencing or boxing in order to gain strength were advised to learn dancing so that they might also acquire physical grace and personal control. “It is a matter of the first importance to the young aspirant,” one manual observed, “that he attend to the training and deportment of his body, as well as that of his mind.” A stately bearing, the booklet went on, could offer young men the “command of address” that was the marker of a well-bred gentleman. Such was the reasoning behind the decision of the Annapolis Naval Academy to hire a dancing master in 1898, a move meant to instill America’s future naval officers with the refinement they needed to conduct themselves appropriately both onboard ships and inside drawing-rooms.

But while dancing and deportment showed off masculine accomplishments, a woman’s demeanor could purportedly reveal the truth about her inner self. As one Rev. Charles Kingsley explained, “if manners make the man, manners are the woman herself … they flow instinctively, whether good or bad, from the instincts of her inner nature.” Dancing, according to the writer Florence Hartley, was an essential womanly skill. “No woman,” she advised, “is fitted for society until she dances well; for home, unless she is perfect mistress of needlework; for her own enjoyment, unless she has at least one accomplishment to occupy thoughts and fingers in her hours of leisure.” A young lady, Hartley continued, ought to inhabit a graceful demeanor whenever she found herself in the public eye. One should, for example, strive avoid such unladylike performances as “sucking the head of your parasol” in the street.

Beginning in the early twentieth century, dance in the United States began to serve another purpose as well, one that was key in shaping ideas about the American national character. As a wave of immigrants arrived in the United States, social reformers worried that newcomers would not be properly assimilated into the fabric of American life. Dance, which psychologist G. Stanley Hall referred to as “the most educative of all because it places the control of the muscles under the will,” worked to impart middle-class American values to the children of these new residents.

Taking up the mantle of what was called the “Americanization” movement, orchestra conductor Meyer Davis invented an “Americanization dance” in which various styles combined to form “an American dance to be danced to American music in America by Americans.” But social workers also emphasized the values of the American “melting pot.” They argued that immigrants brought their own “gifts” which, if preserved, might contribute to the advancement of the nation as a whole. As reporter Helen Bullitt Lowry explained, “the Pole who remembers his mazurka is a better American citizen than the Pole who has traded his mazurka for the American ‘toddle.’” Schools, settlement houses, and women’s clubs across the nation held festivals in which young people performed their national folk dances and took part in patriotic pantomimes, celebrating American unity through cultural and ethnic diversity.

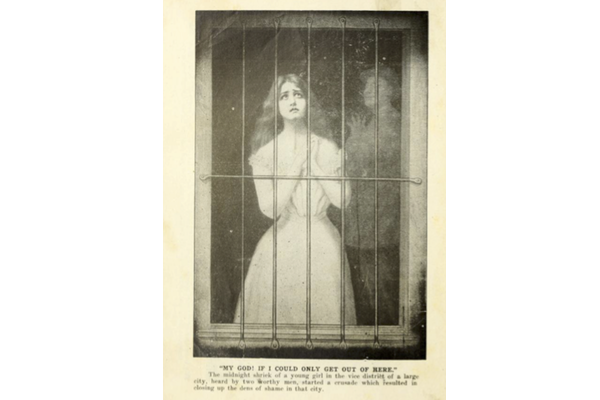

But if proper forms of dancing could teach good citizenship, then improper forms could pose a serious threat to the racial hierarchies embedded in American life. Following the “White Slavery” Mann Act of 1910, a law which forbid the interstate transport of women “for any immoral purpose,” critics warned young women to beware of the dangers posed by mixed-race dance halls. In Chicago, investigative journalist Genevieve Forbes observed the activities in one such “black and tan.” Recalling a “little white girl” who was dancing in the arms of “a large colored man,” Forbes wrote that the young woman “nestles her blonde curls against his coat. Arms interlocked, bodies pressed close together, she gets some of the ‘loving’ she desired.” In the eyes of contemporary observers, such scenes jeopardized the forward progress of American civilization. Endangering white feminine purity and masculine authority, the crude “barbarisms” of jazz music threatened to ensnare American youth deep inside its web.

Later, after World War II, dance was once again called upon to help secure and grow the American way of life. As I explain in my dissertation “Hot Bodies, Cold War: Dancing America in Person and Performance,” the State Department enlisted American dance companies to help establish U.S. supremacy against the rising power of the Soviet Union. Performing in a Russian-dominated art form that was older than the independent United States itself, ballet companies worked to prove that the U.S. system could offer cultural accomplishments as well as capitalist dollars. The innovative movements of modern dance companies showed that the United States could produce new art forms as well score in their performances of the old. And folk dance troupes worked to represent cultural authenticity, showing the world the varied ethnicities that contributed to a thriving American way of life.

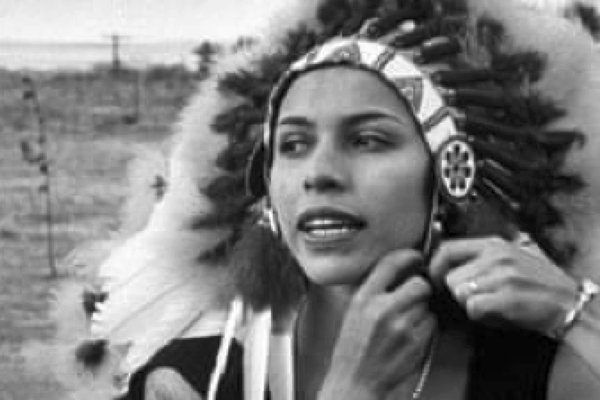

However, although U.S. commentators called dance an “international language” whose value and meaning transcended politics, these tours were part of a concentrated effort to counter perceptions of U.S. racism and portray the country as a land of progressively equal opportunities. In 1954, the same year that the program “Operation Wetback” relied on racial stereotypes to justify the mass deportation of Mexican workers, Mexican-American modern dancer José Limón emphasized the cultural bonds uniting the United States with South America. In 1960, while the U.S. government sought to eradicate Native American tribal authority at home, the famous “American Indian” ballerina Maria Tallchief performed a balletic version of integrative U.S. expansionism matched with an appealing, all-American exoticism. Two years later, while touring in the Soviet Union at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, African American dancer Arthur Mitchell performed an intimate pas de deux, or dance for two, with the white ballerina Allegra Kent. Although U.S. television producers refused to broadcast Mitchell dancing with a white partner at home, the State Department framed this performance as an authentic representation of American democracy abroad.

Maria Tallchief

In more recent days, President Trump’s awkward participation in a traditional all-male Saudi sword dance drew attention on social media, while CNN’s Jake Tapper criticized former President Barrack Obama for his carefree dancing at a Beyoncé concert. In both cases, commentators drew on standard racial stereotypes of dancing men. The powerful white man’s uncompromising self-control translated to hip immobility, while the unrestrained black man’s free movements revealed his lack of personal restraint. Critics of Ocasio-Cortez have also relied on stereotypical gender norms, evoking beliefs that a woman’s bodily movements reveal her true character. Conservative fixation with exposing Ocasio-Cortez as a fraud have also extended to mocking her clothes, calling her a “little girl,” and implying that a high school nickname proves that she is not the person she claims to be, and most recently, a nude phtoto hoax. Because Ocasio-Cortez’s ideas represent a threat to the traditional standards of wealth, race, gender, and social power, her critics argue that her unrestrained body reveals the truth about her self—that she is not the capable young politician she appears to be but is instead an unintelligent and frivolous woman woefully ill-equipped for power.

Viewers are encouraged to subscribe and join the conversation for more insightful commentary and to support progressive messages. Together, we can populate the internet with progressive messages that represent the true aspirations of most Americans.