by Neil deBause

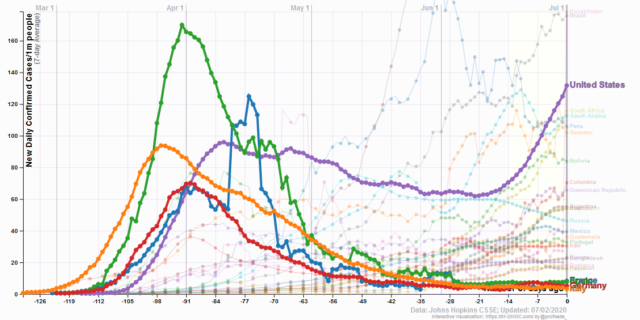

In the second half of June, the story of the United States’ coronavirus pandemic began to shift dramatically, as a massive surge in new infections took hold, particularly across states in the South and West that had previously been spared the worst of the outbreak. Media reports abruptly switched gears from declaring that reopening was proceeding with few ill effects (Reuters, 5/17/20; Tampa Bay Times, 5/28/20) to expressing alarm that health officials’ warnings against lifting social distancing restrictions too soon had been proven right—a cognitive dissonance perhaps most dramatically depicted in Oregon Public Broadcasting’s headline, “Oregon’s COVID-19 Spike Surprises, Despite Predictions of Rising Caseloads” (6/10/20).

Increasingly, the big story has been the litany of state moves to halt or roll back reopenings: A typical roundup in the New York Times (6/26/20) included closing bars in Texas and Florida, a full stay-at-home order in California’s Imperial County, and putting beaches off-limits in Miami-Dade County for the July 4th weekend.

“This is a very dangerous time,” declared Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio, where new cases began rising on June 15, just over a month after the state allowed stores and businesses to reopen. “I think what is happening in Texas and Florida and several other states should be a warning to everyone.”

But a warning of what? While the question of how quickly to reopen will affect potentially millions of lives, equally important is asking what science can tell us about how to reopen. Health experts point to many lessons we can learn from the pandemic experience, both in the US and elsewhere, that can help inform which activities are safest (and most necessary) to resume—a discussion that is more useful than the media’s inclination toward simple debates about whether reopening is good or bad (LA Times, 5/14/20; New York Times, 5/20/20).

Among the most important conclusions:

1. Types of reopenings matter

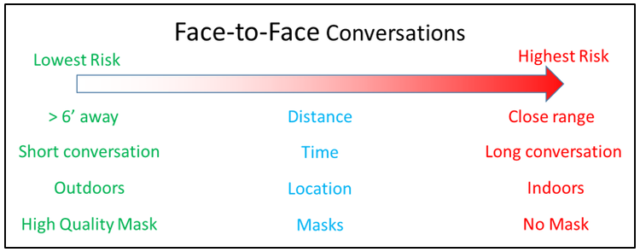

While the coronavirus that causes Covid-19 at first seemed like an all-powerful threat that could be carried by everything from cardboard boxes to cats, public health officials have long since determined that infection is overwhelmingly via person-to-person encounters. This means that reducing face-to-face interaction time—or ensuring that it’s at least conducted while wearing masks, or in outdoor or well-ventilated spaces—is key to reducing risk, as spelled out in a diagram by University of Massachusetts/Dartmouth infectious disease researcher and blogger Erin Bromage:

Infectious disease experts have attempted to reduce this equation to simple mnemonics that will be easy to remember; Tulane University epidemiologist Susan Hassig has cited “the three D’s: diversity, distance and duration” (Business Insider, 6/8/20), while Ohio State’s William Miller created the rhyme “time, space, people, place” (NPR, 6/23/20). These were featured in the increasingly common articles attempting to rank which activities were riskiest, including some that assigned weirdly specific point scales to behaviors for anyone wondering whether they should go bowling or for a pontoon boat ride (MLive, 6/2/20).

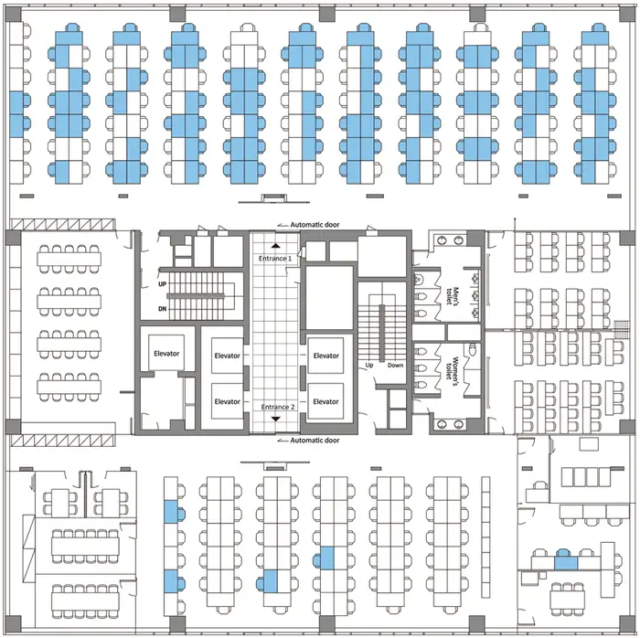

But most of those articles entirely ignored one of the most widespread reopening activities: going back to work in shared office spaces. Infectious disease experts say that offices can be the perfect petri dishes for viral spread, involving gatherings of a large number of people, indoors, for a long time, with recirculated air. As one study (Business Insider, 4/28/20) of a coronavirus outbreak at a Seoul call center showed, the virus can quickly spread across an entire floor, especially in a modern open-plan office. In fact, the call center was doubly prone to viral spread, because its workers were all talking constantly, which previous studies have found to spread respiratory droplets just as effectively as coughing (Better Humans, 4/20/20)—a warning that was heavily noted in media’s coverage of the risks of chanting protestors (Washington Post, 5/31/20; Politico, 6/8/20), but notably missing from articles on the reopening of workplaces.

“They’re pretty high-risk spaces,” Boston University School of Public Health epidemiologist Eleanor Murray tells FAIR. “What we would like to see with offices, if people have to be there for the function of the office to work, is to keep the minimum number of people in at any given time.” (She also urges consideration of the risk to office cleaning workers, who are seldom included in back-to-work safety debates.)

This is especially key, adds Tulane’s Hassig, in office environments where co-workers are breathing the same air. Workers can safely unmask if they’re in a private office where they can shut their door, she tells FAIR; however, “if you’re in an open office space with little four-foot cubicle walls, everybody needs to be wearing masks all the time.”

Yet most states have limited themselves to following CDC guidelines for reopening offices, which mandate wearing masks only when within six feet of a co-worker. But as Bromage (5/6/20) has pointed out, “Social distancing rules are really to protect you with brief exposures or outdoor exposures.”

In fact, former Arizona Department of Health Services director Will Humble told Newsweek (6/9/20) that one reason his state became the nation’s leader in new infections per capita was that local officials did not go beyond CDC mandates to impose “performance criteria such as required business mitigation measures, contact tracing capacity or mask-wearing.” Hassig worries that the CDC’s guidance may have been “far less prescriptive than they would like it to be from the scientific perspective,” noting that “we’ve got plenty of evidence that distance is not enough if you’re in a shared space with lots of people.”

All of this would have been good for US workers returning to their jobs to know, but very little of it has made it into media coverage of reopenings, whether before or after the recent virus spikes. And the rare exceptions often left much to be desired: When CBS News (5/28/20) devoted time to investigating the dangers of reopening offices, it was solely in terms of whether plumbing systems left stagnant during closures could lead to the spread of Legionnaires’ disease.

2. Let science, not political power, guide health decisions

Because it takes at least two to three weeks for case numbers to noticeably rise in response to a change in social distancing rules, Hassig says, states should start slowly, and wait to see if numbers rise before moving on to the next stage of reopening. “If your reopening timetable is preset, that’s somewhat of a folly,” she says. Ideally, she says, after each change in policy, states should “wait at least three weeks to make a decision before you move on, which would mean that probably you’re really looking at a month in each phase. And that is not what Texas did.”

It’s also not how the Texas media presented reopening plans to the public. The Austin American Statesman (4/27/20, 5/1/20) dutifully listed types of businesses that would resume operations under Gov. Greg Abbott’s reopening order, but never cited any independent health officials on the risks each activity would entail. When the Dallas Morning News (4/30/20) ran answers to reader questions about the reopening, the only potential negative consequence it mentioned was whether Texans who refused to return to work could still get unemployment benefits. And the Houston Chronicle (4/30/20) declared, “No more stay-home. Just stay safe”—though the only “safety” measures it mentioned were those still being recommended by Abbott, such as wearing masks in public and limiting the size of gatherings.

The New York Times (5/1/20), meanwhile, chose to both-sides the issue with a story headlined “A Texas-Size Reopening Has Many Wondering: Too Much or Not Enough?”

In doing so, the media largely followed the lead of elected officials, who in many cases let concern over profit-and-loss statements take precedence over whether the data indicated it was safe to resume business as usual. In Ohio, state officials went so far as to allow guidelines to be written by the businesses seeking to reopen themselves (Columbus Dispatch, 6/29/20), something health experts suspect helped lead to a tripling of daily new cases in the state between June 14 and June 25.

3. Learn from places that have done better

The Covid curves in many European and Asian nations that were hit the earliest and took the first and strongest action have remained low, despite reopenings in those nations: Italy, for example, once the world epicenter of the virus, currently has under three new cases per day per million residents, according to Johns Hopkins data—about half the infection rate for the least-hard-hit US state, Vermont.

Those nations, however, took very different approaches to reopening than the US. First off, they waited until case rates were much lower before reopening: When Italy first reopened restaurants on May 18, its daily new-case rate, averaged over the previous week, was 14.4 per million residents; when Florida did so on May 4, its average daily rate was 31.7 per million. “Where you start in terms of your case burden will probably wind up being one of the best predictors of how well your reopening went,” says Hassig.

In addition, the measures the European nations took to get cases down that low were much stricter than those ever implemented in the US—something that was largely overlooked in rundowns of nations imposing and lifting lockdowns (New York Times, 6/10/20; CNBC, 6/25/20). “What we were doing in the US compared to what Europe was doing in terms of lockdown are completely different things,” says Murray:

I have friends in France, and you had to have a permit that said what time you were allowed to go to the grocery store. So even the places in the US that did a gradual opening were already starting from a much more open place than places in Europe.

US residents can also learn from areas of their own country that have done comparatively well under reopenings. Hassig notes that New Orleans and neighboring Jefferson Parish have provided an unintentional controlled experiment—albeit “a sample of one”—in the efficacy of wearing masks: “The mayor of New Orleans made masking mandatory in indoor spaces, which empowered businesses to put up signs like ‘No mask, no shoes, no shirt, no service.’”

The city, which had been an early Covid hotspot, also established a hotline to report violators, kept casinos closed longer, and kept tighter restrictions on such things as church gatherings—with the result, says Hassig, that Orleans Parish currently has less than half the new-case rate of the similarly sized Jefferson Parish. (On Monday, Jefferson Parish announced its own mandatory mask order—New Orleans Advocate, 6/29/20.)

4. Every reopening is a tradeoff

When media outlets posit the decision facing states as balancing the economic needs with public-health needs, it not only ignores that an out-of-control pandemic would be an economic catastrophe (Guardian, 3/26/20), but overlooks another important point: In reopening, governments have a limited amount of risk they can safely spread around without losing control of an outbreak. As a result, reopening decisions don’t just impact public health and the economy now—they also could end up undermining your ability to reopen other things down the road.

“It’s not ‘open’ or ‘shut’—there’s a whole spectrum in between,” says Murray. “We need to be thinking about what are the high-priority things that we need to reopen from a functioning point of view, and not an enjoyment point of view.”

If the goal is to prevent the kind of explosive surge in Covid cases that many states saw in March and April—and which are now being repeated in new hotspots in June and July—that means picking and choosing carefully, not just which activities are the safest, but which are the most urgent for a functioning society—which, it bears emphasizing, is not the same thing as what’s best for businesses’ bottom lines.

“We need to be getting dentists’ offices open and getting childcare open and getting elective medical treatment open; bars are not as important,” advises Murray. “It may be that we have to give up on some of those things to allow the risks that some of these other activities take.”

That’s a discussion that will require informed public debate on the conditions of reopening, from what should stay closed to whether to require masks. It’s a debate that will be much easier if the media spends less time on who is “winning” or “losing” in the struggle to reopen, and more on why people are getting infected—and how they could not be.

Viewers are encouraged to subscribe and join the conversation for more insightful commentary and to support progressive messages. Together, we can populate the internet with progressive messages that represent the true aspirations of most Americans.